The 228 Incident: A Tragedy Exploited by Political Narratives

Beyond the simplified stories weaponized to sow division.

The February 28th Incident (commonly known as the 228 Incident) remains one of the most misunderstood events in Taiwan’s modern history. Both pro- and anti-China commentators in the West frequently misrepresent it, often repeating narratives shaped by certain political interests rather than historical accuracy. These misunderstandings are further exacerbated by a linguistic barrier, since there is little information available about the 228 Incident in English.

A good example of an anti-imperialist unintentionally repeating Taiwan separatist lies can be found in William Blum’s book Killing Hope. Blum, a respected critic of US imperialism, nevertheless echoed misleading claims about the 228 Incident. On page 22 of his book, he writes:

The Generalissimo, his cohorts and soldiers fled to the offshore island of Taiwan (Formosa). They had prepared their entry two years earlier by terrorizing the islanders into submission—a massacre which took the lives of as many as 28,000 people.

In the appendix, he writes:

In 1992, the Taiwan government admitted that its army had killed an estimated 18,000 to 28,000 native-born Taiwanese in the 1947 massacre.

This interpretation oversimplifies a complex historical episode, failing to account for the broader socio-political context and the multiple parties involved in the violence.

The Conventional Narrative and Its Shortcomings

The widely accepted summary of the 228 Incident is as follows: On February 27, 1947, a woman selling untaxed cigarettes was confronted by enforcement officers from the Tobacco Monopoly Bureau. During the altercation, she was struck with a rifle, sparking the anger of bystanders. The next day, protesters gathered to demand justice, leading to a confrontation in which Kuomintang (KMT) soldiers opened fire, killing civilians. According to this narrative, the KMT then launched a mass crackdown, indiscriminately killing tens of thousands of Taiwanese civilians.

However, this version of events omits critical details and presents a highly selective interpretation. While the 228 Incident was indeed a tragic chapter in Taiwan’s history, it was not a one-sided massacre but a series of violent confrontations involving multiple factions. Understanding the full scope of events requires an examination of Taiwan’s demographic composition, political landscape, and the broader historical context of the time.

Demographic, Historical, and Political Context

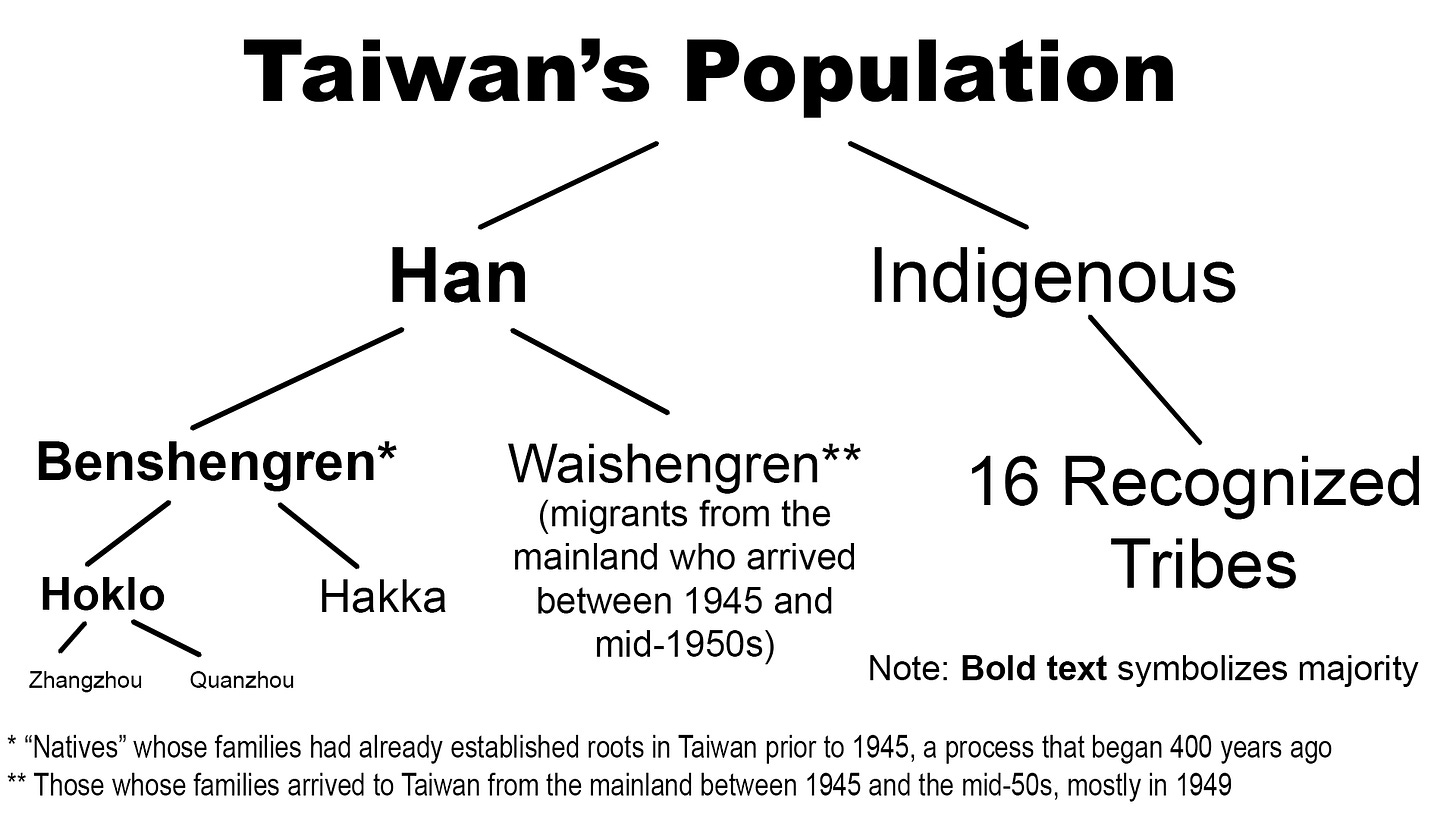

A major source of confusion in English-language discussions of the 228 Incident arises from terminology. Reports often describe the victims as “native Taiwanese,” which some Western readers misinterpret as referring to Taiwan’s indigenous population. This misunderstanding has led some to portray the incident as a genocide against Taiwan’s Indigenous peoples, despite no historical evidence supporting such a claim. Many with this misinterpretation of facts often arrive at the erroneous conclusion that Taiwan’s current population is majority Han because of a genocide carried out by the KMT, but this cannot be further from the truth. Most of the chaos that occurred during the incident happened in urban areas of Taiwan, while the indigenous population, predominately rural and residing in the island’s mountainous and remote regions, was largely unaffected. Therefore, this historical event cannot be described as a genocide against Taiwan’s indigenous population.

In reality, Taiwan’s population at the time was already predominantly Han, divided into two main groups: benshengren (people with ancestral roots in Taiwan before 1945) and waishengren (mainlanders who arrived to Taiwan following 1945, with most of them arriving in 1949). The benshengren category can be further subdivided into Hoklo and Hakka communities. Hoklo are descendants of migrants from southern Fujian Province, and the Hakka people in Taiwan largely hail from the Hakka areas of Guangdong Province. Benshengren made up the majority of the population, but had not yet been integrated into government, whereas waishengren were in an extreme minority until 1949, when their numbers increased to roughly 20% of Taiwan’s population. However, from 1945 until 1991, waishengren dominated upper levels of government in Taiwan, therefore despite the fact that the vast majority of waishengren were not in positions of power, they were nonetheless associated as a group with the elites who ran Taiwan.

Political tensions in Taiwan were exacerbated by economic instability, corruption, and cultural differences between the benshengren and the newly arrived waishengren. Many Taiwanese had initially welcomed the return to Chinese rule after fifty years of Japanese colonization, but their optimism quickly faded due to economic mismanagement, inflation, and the poor conduct of KMT soldiers. Taiwan, which was already a war-torn island, was left in a state of further disrepair, significantly hampering its economic recovery in the early years of KMT rule and creating fertile ground for discontent toward the incoming Chinese government to take root.

These underlying grievances created a volatile environment leading up to February 1947.

The Four Phases of the 228 Incident

A more comprehensive understanding of the 228 Incident divides it into four distinct phases:

The Initial Incident and Protests:

The confrontation over illegal cigarettes on February 27, 1947, escalated when an enforcement officer fired his weapon, fatally wounding a bystander.

Protests erupted the following day, with demonstrators demanding governmental reforms, including constitutional governance and greater political representation for Taiwanese.

The government’s refusal to engage with protestors led to violence, as soldiers fired into crowds, killing several people.

Riots and Targeted Violence Against Mainlanders:

What began as protests devolved into riots, with demonstrators seizing government buildings and radio stations.

Amid the chaos, groups of lumpen-proletariat benshengren targeted waishengren civilians, including teachers, civil servants, and their families.

Reports document instances of mainlanders being beaten, murdered, and in some cases, raped. Language was often used to identify mainlanders, with individuals unable to speak fluent Hokkien or Japanese being attacked.

Military Suppression:

On March 8, reinforcements from the mainland arrived to Taiwan to quell the unrest.

Soldiers engaged in violent suppression, indiscriminately arresting and executing those suspected of involvement in the uprising.

While the government sought to restore order, excessive force resulted in civilian casualties.

Betrayals and Settling of Personal Scores:

Some Taiwanese individuals exploited the chaos to falsely accuse rivals or personal enemies of being anti-government conspirators.

This led to additional arrests and executions, deepening the tragedy.

Phase 1: The Initial Incident and Protests

After being separated from their mainland compatriots for half a century, the people of Taiwan had high expectations for their reintegration with China. However, their first encounters with mainlanders were often disappointing. The first arrivals were poorly dressed soldiers who had come from much lower living standards, creating an immediate sense of disillusionment.

Many of these soldiers were poorly disciplined and unfamiliar with modern infrastructure—some had never even seen elevators before. This cultural and developmental gap was stark. The Taiwanese population, which had been under Japanese rule, spoke predominantly Hokkien or Hakka, while the incoming mainlanders spoke a variety of Chinese topolects. At the time, Standard Mandarin had not yet become widely spoken among the existing population.

Shortly after Taiwan’s return to China, the ongoing civil war between the KMT and the Communist Party diverted government attention away from effectively governing the island. Taiwan’s people faced heavy taxation to support the war effort, while inflation surged. Many civil servants were dismissed and replaced by mainlanders, often underqualified for their roles. This was partly due to the fact that existing civil servants had been educated under the Japanese system and partly due to KMT suspicions regarding their loyalties—especially since many Taiwanese men had been conscripted into the Imperial Japanese Army toward the end of World War II.

Taiwan separatists often attribute early tensions solely to mainlanders looking down on the local population. While some elite mainlanders did harbor such views, the situation was more complex. Many Taiwanese also viewed the impoverished mainland arrivals as backwards, a perspective often omitted in separatist narratives.

Additionally, Japan’s actions in the months leading up to Taiwan’s return exacerbated the island’s difficulties. Though Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945, Taiwan was not officially returned to China until October 25 of that year. During the interim period, Japanese authorities engaged in deliberate acts of sabotage to hinder the incoming Chinese administration. They destroyed infrastructure, dismantled industrial facilities, depleted resources, erased records, and manipulated currency. These actions further destabilized an already war-torn island, severely hampering its economic recovery under KMT rule and fueling dissatisfaction with the new government.

Against this backdrop, the growing discontent culminated in the events of February 28, 1947. The immediate catalyst occurred a day earlier when an enforcement team from the Tobacco Monopoly Bureau in Taipei confiscated illegal cigarettes from a vendor named Lin Jiangmai (林江邁). The altercation escalated when one of the officers struck her with his rifle. As passersby intervened, an officer fired a warning shot to disperse the crowd, but the bullet struck a bystander who died the following day. This incident marked the beginning of the unrest.

In response, protests erupted. On February 28, demonstrators gathered outside the Governor-General’s Office, demanding constitutional governance, the direct election of Taiwan’s provincial governor, and the establishment of a Chinese federation with provincial autonomy for Taiwan. Additionally, they called for greater Taiwanese representation in the government and the public execution of the officers involved in the cigarette vendor incident.

While some demands were reasonable, the call for public executions was an extreme measure that no government would readily concede. The authorities refused to comply, and tensions escalated. Soldiers opened fire on the crowd, killing several protestors.

What began as a protest soon turned into widespread rioting. Demonstrators seized government buildings, military bases, and radio stations, using the latter to spread news of the uprising. As the message spread across the island, the unrest quickly escalated into a full-scale revolt.

These events laid the foundation for a deepening divide between the local Taiwanese population and the mainland-led government, tensions that would shape Taiwan’s political trajectory for decades to come.

Phase 2: Riots and Targeted Violence Against Mainlanders

The mainstream narrative surrounding the 228 Incident often downplays this very critical phase of the 228 Incident, which was the wave of violence against mainlanders (waishengren) in Taiwan. From February 28 to March 8, Taiwan was in a state of anarchy, with rioters acting unchecked. While those in power had protection, ordinary mainlanders in Taiwan—civil servants, teachers, shopkeepers, and other civilians—lacked such safeguards. Since this occurred before 1949, the mainlander population was relatively small.

During this period, many mainlanders were brutally beaten, murdered, and even subjected to sexual violence. Documented cases include children from mainland families being killed by local rioters. Many of these rioters were former conscripts in the Japanese military who, upon returning to Taiwan, faced unemployment and uncertainty. Frustrated and disillusioned, some took out their anger in a violent and destructive manner.

Under Japanese rule, Taiwan was governed by an industrialized empire that, after decades of suppressing revolts, pursued an assimilation policy. Those who successfully adopted Japanese culture had better opportunities. This program ended in 1945, but its impact lingered, particularly among those conscripted into the military and heavily indoctrinated. After the war, with Taiwan returned to China, some who had embraced Japanese identity faced an existential crisis. The incoming government, weakened by years of war against Japan, was impoverished and struggling with internal issues, further fueling resentment among certain groups in Taiwan. For some, the 228 Incident became an opportunity to exact revenge on mainlanders.

To identify mainlanders, rioters would ask individuals in Hokkien where they were from. Those who responded in broken Hokkien or Mandarin were often targeted. Even some mainlanders from Hokkien-speaking regions on the Mainland such as Xiamen were scrutinized for minor accent differences. In such cases, the rioters would switch to Japanese—asking, “あんたどこの人が” (anta doko no hito ga), meaning “where are you from?” If the individual did not understand, it was assumed they had not experienced Japanese colonization and was therefore a recent arrival.

Among the many brutal cases, one involved a teacher from the mainland in present-day Daxi District, Taoyuan City, who was gang-raped by local rioters. Another involved a woman carrying a child; the child was thrown into a ditch and killed, followed by the mother's murder. These incidents, along with many others, are often downplayed in media and textbooks due to their inconvenient implications for the separatist narrative.

The selective framing of the 228 Incident serves to reinforce a particular political narrative. If these acts of violence against mainlanders were acknowledged as widely as the subsequent military suppression, the simplistic portrayal of 228 as an indiscriminate massacre of Taiwanese civilians by the KMT would be undermined. This is not to justify the actions of either side but to highlight that both mainlanders and local Taiwanese were victims and perpetrators. The true history of 228 is far more complex than the dominant narrative suggests.

Despite the tragedy's historical complexity, the 228 Incident is often portrayed as an event where peaceful intellectuals were violently suppressed. However, this framing ignores the atrocities committed by local rioters.

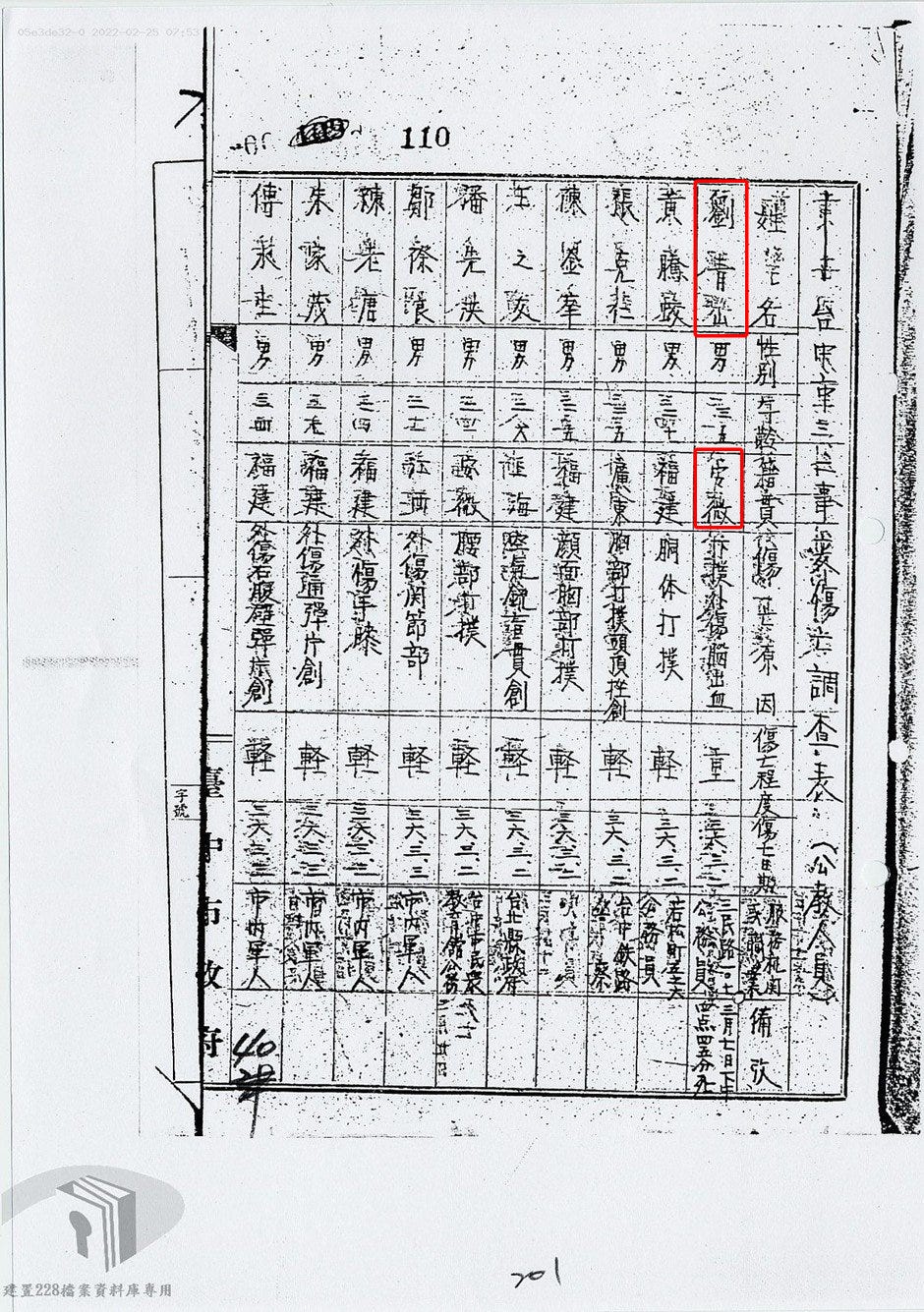

In the 1990s, after martial law was lifted, Taiwan's “Executive Yuan” commissioned an official report on the 228 Incident under Lee Teng-hui’s administration. However, this report selectively amplified accounts of Taiwanese victimization while downplaying documented cases of mainlander victims. One striking example from Taichung involved a civil servant, Liu Qingshan (劉青山), whose hometown was deliberately omitted from the report. He was brutally mutilated and left to die—yet because he was from Anhui Province, his mainland origin was erased to fit a narrative of mainlanders oppressing Taiwanese.

This selective history has influenced both domestic and foreign understandings of the event. For example, William Blum’s book erroneously frames the incident as the KMT terrorizing the island to cement dominance, largely due to flawed sources that relied on the official government report.

For decades, discussion of 228 was banned in Taiwan. Consequently, many in the boomer generation only learned fragments of the event in a hushed manner. This silence allowed opposition figures to reshape the narrative to their advantage, leading to generations of Taiwanese—especially younger ones—being misled about the full scope of the tragedy.

Today, separatist groups use the 228 Incident to impose collective guilt on waishengren while absolving benshengren of any responsibility for the violence. However, if waishengren are expected to bear collective guilt for the actions of KMT soldiers, why shouldn't benshengren bear similar responsibility for the atrocities committed by local rioters?

Starting in the 1990s, some waishengren publicly apologized on behalf of all mainlanders for 228. This raises questions: What gives these individuals the right to apologize for an entire group? Many waishengren families had no connection to the event, as the majority arrived to Taiwan in 1949. Additionally, many mainlanders who were in Taiwan at the time and survived the chaos fled back to the mainland after 228, a fact rarely acknowledged in mainstream discourse.

The most troubling aspect is how 228 is commemorated in the media. While ostensibly meant to promote historical understanding and reconciliation, the narrative instead fosters division by continuously framing the incident as a one-sided massacre of Taiwanese civilians by KMT forces. The intent appears less about healing and more about reinforcing political identities.

Regardless of how the violence began—whether initiated by the government or by rioters—the island-wide unrest could not be ignored. The suppression, while brutal, was not the simple narrative of an authoritarian crackdown on peaceful protestors that it is often made out to be. A full and honest reckoning with history requires acknowledging the suffering of all victims, regardless of their ethnic or political affiliations.

Phase 3: Military Suppression

With violence erupting across Taiwan, Chiang Kai-shek’s government on the mainland dispatched the 21st Division of the army to restore order. On March 8th, reinforcements arrived, landing in Keelung, a northern port city. This marked the beginning of the third and most well-documented wave of killings.

A key detail about the 21st Division is that many of its soldiers were illiterate peasants from Sichuan who had just fought against the Japanese. When they heard that Taiwanese rioters were murdering people with Japanese swords and expressing pro-Japanese sentiments, it triggered deep-seated resentment. Many of these soldiers harbored intense hatred toward Japan and saw this as an opportunity for retribution. This explains the brutality they inflicted. While nothing excuses the killing of innocent people, this was, in essence, war—always tragic and chaotic.

The soldiers boarded their ship in Shanghai on March 7th, arriving in Keelung the next day. Upon landing, they immediately opened fire. However, what is often overlooked is that they were met with violent resistance. Armed rioters were already at the shore, shooting at them. So rather than an outright massacre, this was a battle. As the soldiers pushed southward—reaching Taipei on March 9th and continuing into other cities—they crushed any resistance in their path.

The characterization of these events as a massacre stems from the 21st Division’s indiscriminate tactics, which included firing into crowds, raiding homes, and carrying out mass arrests. From northern Taiwan to southern cities such as Kaohsiung and Chiayi, their campaign left widespread devastation.

While rioters were among those killed, many civilians also lost their lives. The actions of the 21st Division cannot be excused, but they did succeed in restoring order to Taiwan after a week of lawlessness. A balanced historical assessment must acknowledge that, just as these soldiers engaged in indiscriminate killings, local Taiwanese mobs had, for over a week, similarly perpetrated widespread violence against mainlanders.

Phase 4: Borrowing the Mainlander’s Knife to Settle Taiwanese Scores

The fourth and final wave of killings during the 228 Incident involved instances in which local Taiwanese exploited the presence of mainland—who were largely unfamiliar with the local population—to settle personal disputes.

As the military continued its campaign of repression, some Taiwanese saw an opportunity to eliminate personal adversaries. Many of the newly arrived soldiers were illiterate and unfamiliar with Taiwan, making them susceptible to misinformation. Exploiting this, some locals falsely accused their rivals—whether personal enemies or business competitors—of being anti-government rebels or communist sympathizers.

Eager to demonstrate their effectiveness to their superiors, the soldiers often acted without thorough investigation, leading to widespread arrests, executions, and disappearances of innocent individuals.

This aspect of the 228 Incident is seldom discussed today. A more complete understanding of these events complicates the prevailing narrative, which often portrays local Taiwanese as passive victims and mainlanders as the sole perpetrators. The fourth wave of killings continued throughout March before the unrest gradually subsided.

The Question of Casualties

In 1995, the 228 Memorial Foundation was established to provide compensation and rehabilitation for the victims of the 228 Incident. The application period ended in 2017, with a maximum compensation of NT$6 million (approximately US$180,000) for those who could provide evidence of a family member’s death during the period of unrest. Lower amounts were granted for cases involving disappearances, wrongful imprisonment, or other related hardships.

Taiwan's household registration system, inherited from the Japanese colonial administration, was highly systematic and well-maintained. Given the thoroughness of these records, deaths and disappearances during this period would have been relatively easy to verify. Notably, no city or county reported death tolls reaching the thousands for February and March 1947, and this is operating under the assumption that all deaths that occurred during that time-frame were related to 228. This raises questions about the widely cited estimate of 28,000 deaths.

Despite the significant financial incentive, the total number of approved compensation cases from 1995 to 2017 amounted to 2,792. Among these, 685 cases were for deaths, 180 for disappearances, and 1,437 for imprisonment, injury, or reputational damage. Even if all disappearances were presumed to be deaths, this would indicate a total of 865 confirmed fatalities attributable to military repression. Given the frequently cited estimates of 18,000 to 28,000 deaths, one would expect a much higher number of families to have applied for compensation.

These figures are publicly available on the 228 Memorial Foundation’s website. In contrast, George Kerr—an American diplomat known for his pro-separatist sympathies—estimated 10,000 deaths, while a Nanjing-based delegation in the immediate aftermath of the incident reported a figure between 3,000 and 4,000. Even the higher end of this range remains significantly lower than the estimates later promoted by the Lee Teng-hui administration.

Further inconsistencies can be observed in claims made by Kin Birei (金美齡), a Japan-based Taiwan independence activist who renounced her Taiwan citizenship. In her book Oh, Japan! Oh, Taiwan! (《日本啊!台灣啊!》), she initially cited a death toll of 28,000, yet later in the same text, the number increased to 50,000. Some figures proposed by other sources—such as claims of 100,000 deaths—are entirely detached from historical records.

The official estimate of 18,000 to 28,000 deaths, put forth by the Lee Teng-hui administration, appears politically motivated. The report produced under his leadership placed significant emphasis on violence committed by mainland soldiers against benshengren while downplaying the role of local hooligans in targeting mainlanders. The inflation of casualty figures serves to reinforce a narrative of Taiwanese victimization at the hands of mainlanders, aligning with the broader political objectives of Taiwan’s separatist movement, which was gaining momentum during the era of Lee Teng-hui’s leadership.

The Political Legacy of the 228 Incident

The narrative often presented regarding Taiwan’s history portrays the island as a victim of mainland Chinese brutality, which is used to justify the position that the two sides of the Taiwan Strait are separate entities as opposed to two parts of a whole. According to this framing, Taiwan has endured “Chinese oppression” since 1947, starting with the KMT’s actions, and continuing with the Communist Party of China (CPC) hindering Taiwan’s place on the global stage. This portrayal of Taiwan’s experience as a history of victimhood is oversimplified and disregards the complexities of the island's past.

The exaggerated accounts of the 228 Incident—often described as a massacre by mainlanders—are part of this narrative. It is critical to examine why these stories are inflated and why some deaths are exaggerated while others are downplayed. While any death toll is certainly tragic, the distortion of facts serves an agenda, aiming to vilify the mainland and create a false sense of continual persecution by “Chinese forces.”

For instance, the White Terror period under the KMT is often framed as the indiscriminate slaughter of Taiwanese independence supporters. In reality, however, the primary targets during the White Terror were Communists and suspected Communists, many of whom were mainlanders, not local Taiwanese. The true statistics show that more mainlanders in Taiwan were executed for political crimes than benshengren. Therefore, the claim that the White Terror was a one-sided campaign against local Taiwanese is misleading.

The focus on victimhood and oppression has led to an environment where people are pitted against each other. Descendants of mainlanders are often accused of being complicit in violence against local Taiwanese, but if we are to play this game, it’s important to consider the violence from both sides. In the case of the 228 Incident, the number of casualties among both mainlanders and local Taiwanese was similar. If the military's actions during the suppression of the chaos are characterized as a massacre, the senseless violence against mainlanders by local Taiwanese hooligans should be viewed in the same light.

As the 78th anniversary of the 228 Incident approaches, it’s important to acknowledge the role misinformation plays in shaping perceptions of Taiwan’s history. Many of the narratives, particularly those promoted by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), have become widely accepted, even by some who consider themselves pro-China, due to the lack of accurate information in English. This narrative fosters division not only between Taiwan and the Chinese mainland but also within Taiwanese society.

A key myth that has been perpetuated by some pro-China westerners is the idea of a “genocide” during the 228 Incident, often described as the wholesale slaughter of indigenous Taiwanese by the KMT. However, the reality is that the 228 Incident involved various groups of Han people, both local and mainland, clashing in a violent and chaotic manner.

I am not interested in defending the KMT or local Taiwanese extremists, but simply aim to defend the truth. The story of Taiwan’s history is often distorted, and these lies spread quickly, sometimes unintentionally, by well-meaning individuals. It’s essential to understand how easily misinformation can proliferate and how it can shape public opinion.

If you find yourself encountering claims about the KMT committing genocide against Taiwan’s indigenous people, I encourage you to share this information to help spread the truth. Only by confronting these falsehoods can we create a more accurate and nuanced understanding of Taiwan's history and, by extension, China’s history.

Conclusion

The 228 Incident was a tragic and complex episode shaped by political, social, and economic factors. While the actions of KMT forces were unquestionably brutal, the widespread portrayal of the event as a one-sided massacre is historically inaccurate. Understanding the full context—including the violent actions of benshengren rioters against waishengren civilians—is crucial for an honest reckoning with history.

Rather than using 228 as a political tool to deepen divisions, Taiwan’s society would benefit from a more nuanced and factual approach to this historical tragedy. Only by acknowledging the full scope of events can a more comprehensive and truthful historical memory be preserved.

Thank you for this excellent article. I visited the 228 Museum a few months ago and it was evident, even for someone like me, who is completely new to Taiwanese history, that the narratives that are pushed today are somewhat simplistic and skewed, if not weaponised. Your article helps unpack and clarify these narratives.