From Majority to Minority: The DPP’s Struggle to Accept Reality

The “Political Chaos Laws” and the DPP’s Manufactured Crisis

The current political landscape in Taiwan presents a complex and contentious dynamic, particularly in light of recent legislative developments. Under the leadership of Lai Ching-te (賴清德), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) appears increasingly unwilling to engage in the necessary compromises inherent to the very liberal democracy it once fought for. This marks a stark contrast with his two DPP predecessors, Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) and Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁), who navigated Taiwan’s political intricacies with a more strategic approach.

Tsai Ing-wen, despite being a DPP leader, maintained relationships with key figures in the Kuomintang (KMT) and understood the importance of balancing the political forces within Taiwan. Her political journey began as a bureaucrat under KMT rule, and she was closely associated with former leader Lee Teng-hui (李登輝) before joining the DPP in 2004 while working under Chen Shui-bian. This experience granted her a pragmatic understanding of governance that informed her leadership.

Similarly, Chen Shui-bian, the first DPP leader of Taiwan, recognized the necessity of cooperation when he assumed office in 2000. At the time, the DPP was in the minority within the legislature, necessitating a more conciliatory approach. However, under Lai Ching-te, the DPP appears to operate under the assumption that controlling the executive branch grants them the right to override opposition, despite holding only 51 out of 113 legislative seats.

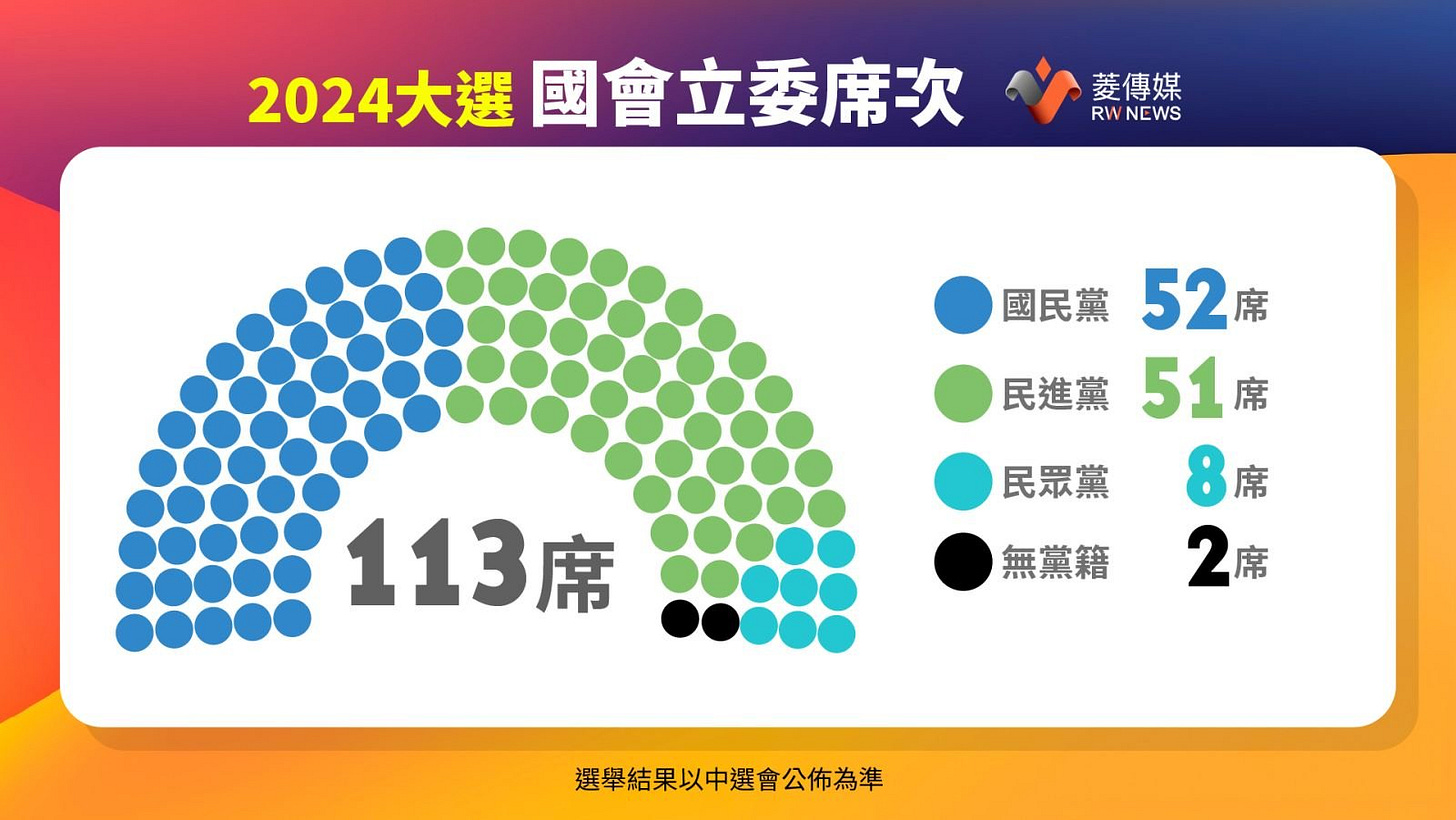

The opposition, primarily composed of the KMT with 52 seats, does not hold an outright majority either. The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), a new third party, holds 8 seats and has effectively positioned itself as a deciding force in the legislature, and is currently in a de facto united front with the KMT against the DPP. Additionally, two independent legislators have similarly opposed the DPP’s initiatives. Together, these factions constitute a 62-seat majority against the DPP’s 51.

This dynamic has placed the TPP in a position of considerable influence. Given that the DPP and KMT frequently vote in opposition, the TPP often acts as a tiebreaker. The DPP has responded to this reality with hostility, launching a campaign against Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) and accusing the KMT-TPP alignment of being anti-democratic.

The recent election of KMT’s Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜) as the speaker of the legislature further underscores this political realignment. Han secured his position with 54 votes to 51, largely due to the TPP abstaining in the second round and the two independents supporting him. In response, DPP supporters accused the TPP of undermining democracy simply for failing to support their preferred candidate. This reflects a broader trend in the DPP’s rhetoric: any opposition to their agenda is labeled as undemocratic or even as collaboration with external forces.

The DPP Reacts to the Three “Political Chaos Laws”

A recent point of contention involves the KMT and TPP successfully amending three key laws:

The Public Officials Election and Recall Act

The Constitutional Court Procedure Act

The Act Governing the Allocation of Government Revenues and Expenditures

Despite the fact that these amendments were passed through democratic processes by a legislative majority, the DPP has accused the opposition of imposing its will through undemocratic means. This narrative underscores the DPP’s growing reluctance to acknowledge legitimate democratic opposition and its increasing tendency to frame political disagreements in existential terms.

The acting director of the DPP’s Department of International Affairs, Michael Chen (陳文昊), has publicly echoed these sentiments, claiming that these amendments will make it impossible to recall public officials, paralyze the constitutional court, and serve the interests of the Communist Party of China. However, a historical examination reveals that the DPP itself has advocated for similar reforms in the past. His comments reflect the DPP’s broader strategy of dismissing political opposition as illegitimate rather than engaging with the realities of Taiwan’s divided government.

A recent statement from the official DPP Twitter account reads:

The KMT and TPP forced through a trio of “political chaos laws” with no regard for legislative due process. They violently assaulted DPP legislators and forcibly imposed their will through undemocratic means. The DPP condemns their utter disdain for Taiwanese democracy. By ignoring parliamentary procedures and tarnishing the legislature’s dignity, the KMT and TPP have caused immense harm to our democracy. The DPP calls on all citizens to stand against their reckless actions and protect Taiwan’s democratic values.

In electoral politics, a minority party is traditionally expected to accept legislative setbacks and focus on future electoral victories to enact its policies. However, the DPP is now framing this situation as undemocratic. What is notably absent from both the tweet and Michael Chen’s statements is the fact that DPP legislators initiated the violence on December 20th by smashing three windows, forcibly entering the Legislative Yuan, and occupying the Speaker’s chair.

Regarding the KMT’s decision to barricade itself in the chamber and prevent the DPP from entering to discuss the amendments, it is worth noting that the DPP employed similar tactics in the past when it held the legislative majority. This reflects the deep divisions between the parties and underscores the reality that legislative success ultimately depends on securing a majority.

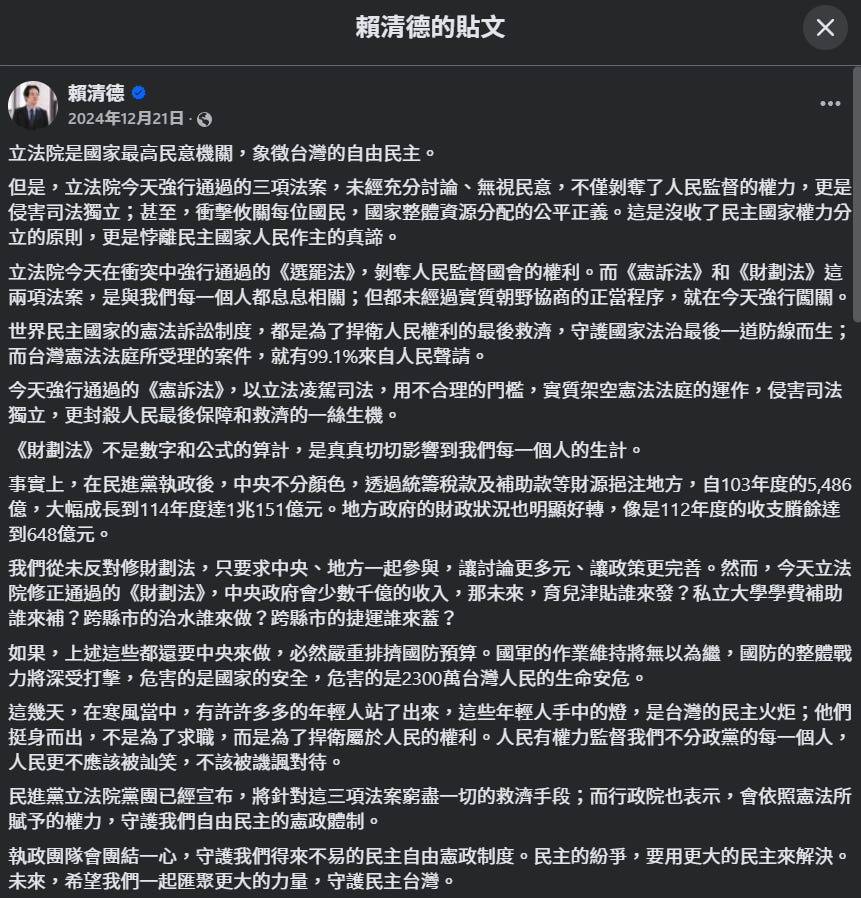

Lai Ching-te, the leader of the Taiwan Area, also weighed in on the situation via Facebook. In his post, Lai argued that the amendments were passed without sufficient discussion or proper procedures, claiming they undermine democratic principles, judicial independence, and fair resource allocation. He specifically criticized the amendment to the Constitutional Court Procedure Act, asserting that implementing a majority-rules principle in the court is an unreasonable restriction. Additionally, he expressed concern that changes to the Government Revenues and Expenditures Act could negatively impact crucial programs, including childcare subsidies, education, infrastructure, and defense spending. Finally, he praised DPP supporters for “standing up for democracy,” despite their participation in obstructing legislation passed by democratically elected legislators.

The reality is that these bills were fast-tracked because the opposition holds the legislative majority. Additional debate would not have changed the outcome. If Lai genuinely seeks greater minority party input, he need only look to the TPP, which holds eight seats in the legislature and is, by definition, a minority party. The DPP, though in the minority, still holds 51 out of 113 seats and has the option of winning over the TPP to secure a majority. However, rather than engaging in coalition-building, the DPP has chosen to mobilize public opinion against the legislature by labeling the opposition as anti-democratic.

A key issue for the DPP is that Lai Ching-te secured only 40% of the popular vote in the most recent election. When accounting for abstentions, this figure drops below 30%. As a result, his ability to rally sufficient public support to influence legislative outcomes is highly limited.

The accusations against the KMT and TPP regarding democratic procedures and legislative violence are also one-sided. While physical altercations did take place, the initial escalation came from DPP members, who broke into the legislature on the night of December 19th, just before the morning session on December 20th, to seize control of the chamber and disrupt proceedings. This move was largely orchestrated by Lai, who also called on DPP supporters to surround the legislature that night. However, he deliberately refrained from having them storm the building, recognizing that such an act would be a public relations disaster given the DPP’s current unpopularity.

Ultimately, the DPP’s strong opposition to the amendments may stem from genuine policy concerns. However, these amendments can be overturned in the future through legislative processes. A more pressing issue for the DPP is that the passage of these bills establishes a precedent for the KMT and TPP working together in opposition to the DPP. This is significant because, for the first time, there exists a third party that is neither a splinter faction of the KMT nor a product of a DPP-sponsored political movement. The emergence of the TPP as a significant legislative force challenges the DPP’s political dominance. The DPP has proven adept at defeating the KMT in elections for Taiwan’s top leadership, but a genuine united front between the KMT and TPP would pose a serious threat to the DPP’s long-term influence.

Lai’s Inexperience with Opposition

The DPP under Lai is acting so brashly because Lai has never had experience running a government with a formidable opposition.

Before becoming the so-called “Premier” in 2017 and later the so-called “Vice President” in 2020, Lai’s most notable post in government was Mayor of Tainan City from late 2010 to mid-2017. He won that post in 2010 with 60% of the vote, and Tainan City has never had a KMT mayor since 1997. Since then, the city council has always had a majority of DPP members.

Therefore, as the governor of Tainan City, Lai faced no meaningful opposition whatsoever. When he became the “Premier” of the “Republic of China” in 2017, his job was essentially to manage the executive branch under the authority of Tsai Ing-wen. As a result, he did not call the shots in government at the time. From 2020 to 2024, he was the so-called “Vice President” for Tsai Ing-wen, meaning, once again, he answered to her and did not call the shots.

Even if he had called the shots, during his tenure as Tsai’s deputy leader from 2020 to 2024, the DPP had the majority in the legislature, meaning he would not have had to contend with an opposition-controlled legislature.

Lai’s Rise and the DPP’s Fall

Come 2024, the situation has shifted. Lai won the election with the most votes but not a majority, and the legislature is controlled by the opposition. For the first time since 2008, the DPP is in power while the opposition holds the majority in the legislature, marking a return to power dynamics similar to those of Chen Shui-bian’s leadership from 2000 to 2008. Back then, the legislature was dominated by the opposition just as it is today. At the time, the DPP had won leadership for the first time in 2000 with less than 40% of the vote. With most of society and the legislature against him, Chen knew he had to work and compromise with the KMT-led pan-blue coalition to accomplish anything. He understood that employing tactics similar to Lai’s today would have severely damaged the DPP’s image during its first tenure as the ruling party.

From 2008 to 2016, Taiwan's leadership returned to the KMT with Ma Ying-jeou, and for both of his terms, the legislature was KMT-majority.

2016 marked a major turning point, as it was the first time the DPP controlled both the executive branch and the legislature. This made the DPP more powerful than it had ever been. Public support for the DPP surged, largely due to the 2014 Sunflower Movement, which successfully painted the KMT as a puppet of the CPC. However, by 2019, Tsai Ing-wen was projected to lose re-election in 2020 against Han Kuo-yu, whose popularity skyrocketed in 2018 and 2019. The Hong Kong riots in 2019 changed the political landscape, and the DPP leveraged one-sided media coverage to stoke fears that a KMT victory would turn Taiwan into another Hong Kong under “CPC terror.”

Despite the DPP’s 2020 victory, Tsai’s administration failed to improve the lives of people in Taiwan. From 2020 to 2024, dissatisfaction grew due to rising housing prices, inflation, and widening inequality. Many felt the government was overreaching and exerting excessive control over local city and county governments. Furthermore, a series of high-profile corruption cases involving DPP officials and their associates severely damaged the party’s image.

By 2024, the DPP was governing without the support of the majority of the population and against an opposition-dominated legislature. Talks between the KMT and TPP about running on a joint ticket in 2024 were underway, but ultimately fell through. Had they succeeded, they would have likely won the election. Their failure to form an alliance allowed Lai to win with just 40% of the vote, but with the KMT and TPP working together more closely than ever before, the DPP fears their continued cooperation will prevent the Lai from winning his re-election in 2028 and make it difficult for the DPP to reclaim the legislature.

The DPP’s Aggressive Strategy

One might expect the DPP to compromise with the opposition-led legislature, demonstrating respect for the will of the people and earning their trust for a potential comeback in 2028. Instead, the DPP has launched an aggressive campaign to discredit the opposition. They are branding the KMT and TPP as CPC puppets while targeting the TPP's founder and recently-resigned chairman, Ko Wen-je, with a corruption investigation based on flimsy charges.

The DPP has also adopted a mentality of, “if we can’t win local elections, we’ll just initiate recalls.” Under current laws, to initiate a recall for a legislator, a petition must be signed by at least 10% of eligible voters in his or her respective district. Once initiated, only 25% of eligible voters need to vote in favor of the recall, and if the number of votes in favor exceeds those against, the recall succeeds. This strategy signals a shift away from democratic engagement and towards a more combative, retaliatory approach to maintaining power.

In order to address the DPP’s tactics, the KMT and TPP amended the Public Officials Election and Recall Act.

Amendments to the Recall Process

The changes to the Public Officials Election and Recall Act, proposed by the KMT and backed by the TPP, introduced stricter requirements for initiating a recall. Under the new rules, petitioners must collect photocopies of ID cards when collecting signatures to prevent fraud. Previously, only an ID number and registered address were required, which left room for potential abuse.

Additionally, the revised law stipulates that for a recall to succeed, the number of votes in favor must exceed the number of votes the official originally received when elected. This change prevents the system from being weaponized against officials who won their elections fairly. Under the previous rules, the DPP could lose a mayoral election, gather signatures from just 10% of eligible voters, and, with only 25% turnout in favor, successfully remove a KMT or TPP mayor.

Whether one agrees with these amendments or not, the fact remains that the legislators who passed them were democratically elected by the people. The amendments were voted on and approved by the majority in the legislature, making the process entirely legitimate. Yet, the DPP has labeled the changes “anti-democratic”—a claim that rings hollow when considering their own conduct.

Amendments to the Constitutional Court Procedure Act

One of the key amendments the DPP opposes relates to how Taiwan’s Constitutional Court functions. To understand the issue, it helps to compare Taiwan’s system with the US Supreme Court.

In the U.S., the Supreme Court consists of nine justices, and at least six must be present to decide a case. A ruling requires a majority agreement, meaning five justices must concur for a decision to count. This ensures a majority-rules principle in judicial review.

However, Taiwan’s system operates differently. The Constitutional Court has 15 Grand Justices, but under the current rules, only nine need to be present to hear a case, and just six must agree for a decision to pass. This creates a situation where a minority of justices can dictate rulings, overriding the majority—a structural flaw that undermines judicial balance.

In October 2024, seven Grand Justices retired. Under Taiwan’s system, the “President”—currently Lai Ching-te—must nominate replacements, but these nominees must be confirmed by the Legislature. Since the Legislature is controlled by the opposition, they rejected Lai’s nominees, preventing the Constitutional Court from functioning due to a lack of quorum.

This move was aimed at blocking Lai from stacking the judiciary with loyalists. If all seven of his picks were approved, they alone could control rulings despite being a minority of the 15-justice court.

To prevent this kind of judicial capture, the KMT and TPP introduced amendments to the Constitutional Court Procedure Act that would:

Increase the quorum from 9 to 10 (⅔ of 15), ensuring broader participation in rulings.

Require 9 justices to agree for a decision to pass, preventing a small faction from controlling legal outcomes.

This brings Taiwan’s system closer to the US, where the Supreme Court requires two-thirds (6 of 9) present and a 55% majority (5 of 9) to rule. Under the new rules, Taiwan would require two-thirds (10 of 15) present and a 60% majority (9 of 15) to pass a decision—a standard in line with democratic norms.

Despite these changes being rooted in majority rule principles, the DPP is framing them as anti-democratic. They argue that higher thresholds make it harder for the judiciary to act as a check on executive and legislative power. In reality, the reform is designed to prevent politically motivated rulings from a small group of justices.

Ironically, when Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) was in power, the DPP—then in the minority—pushed for similar judicial reforms, including raising decision thresholds. Once the DPP gained power in 2016, they abandoned those reforms since they now controlled judicial appointments and could use the system to their advantage. Now that they are back in the minority, they are crying foul as the opposition moves to fix the same problems they once identified.

At this point, the DPP’s position is clear: Democracy means whatever benefits the Democratic Progressive Party. If you oppose the DPP, you must be against democracy—because their party has “Democratic” in the name.

It’s the same rhetorical trick used by radical liberals in the US, where criticizing the Black Lives Matter movement is equated with believing that black lives don’t matter—simply because of the name.

Amendments to the Act Governing the Allocation of Government Revenues and Expenditures

The third major amendment concerns the Act Governing the Allocation of Government Revenues and Expenditures, which dictates how resources are distributed between the “central government” and local governments. Under the current system, the “central government” receives 75% of revenues, while local governments are left with 25%. The amendment will restore the previous 60:40 split, which was in place before 1999.

With the “central government” hoarding three-quarters of all revenues, local governments have struggled to address financial challenges effectively. Increasing local governments’ share to 40% would allow for greater financial autonomy, enabling cities and counties to implement solutions tailored to regional needs rather than relying on top-down micromanagement from Taipei. This shift aims to foster independent regional development rather than forcing every locality into a one-size-fits-all governance model.

Once again, the DPP’s shifting stance exposes its opportunism. Back in 1999, when the KMT’s Lee Teng-hui changed the revenue allocation from 60:40 to 75:25, the DPP was against the change, since the DPP controlled more local governments at the time and wanted a larger share of tax revenue. But now that the DPP dominates the “central government” while holding only 5 out of 22 local governments, it suddenly wants to maintain the 75:25 split—a blatant reversal of their past position.

To justify their opposition, the DPP is resorting to fear-mongering. They claim that reducing the “central government’s” share will lead to defense budget cuts, which is baseless. Major military procurements are usually funded through special budgets, and frankly, much of that money is wasted anyway—Taiwan has been strong-armed into buying outdated, overpriced weapons from the US incapable of winning a war with the People’s Liberation Army.

They also claim the change will undermine social programs like retirement funds and health insurance, but this doesn’t hold up under scrutiny either. The “central government” regularly runs tax surpluses, meaning it has more than enough funds to cover existing programs without any reductions. In reality, the DPP’s real concern isn’t fiscal responsibility—it’s losing centralized control over resources, which would strengthen opposition-controlled local governments.

If the DPP truly believes this revenue distribution is flawed, they can change it back to 75:25 once they regain a legislative majority. But instead, they’re branding the KMT and TPP as undemocratic for proposing a policy that the DPP itself once supported—all while inciting chaos and even physical altercations in the legislature.

Conclusion

The common thread in all of these amendments is the DPP’s blatant hypocrisy. Their outrage isn’t about democracy or protecting Taiwan—it’s about losing their grip on power. When they were in opposition, they demanded these exact reforms. Now that they’re in control, they condemn them.

At the end of the day, democracy is not defined by whether the DPP gets its way. It’s about majority rule, checks and balances, and accountability. The DPP has no divine right to rule Taiwan, and just because they don’t like a law doesn’t mean it’s undemocratic. If they want to reverse these changes, they should win a majority in the next election—not throw tantrums and brawl in the legislature like sore losers.

Taiwan’s voters should remember this the next time the DPP claims to be the sole defender of democracy. Because their track record tells a very different story.